All alone are the Framer and the Shaper, Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent...

Popol Vuh

A Continental Myth

The prevailing consensus among those that currently study the Mississippian Era is that this was an isolated event, with no direct influence outside Hopewell or Late Woodland culture or the introduction of some concepts with maize and beans from the Southwest.

“In accordance with prevailing theories, our analysis has convinced us that the concept of a cult in the sense of a unified system of religious practice is no longer viable. And with it may be buried any notion of a Mesoamerican origin for the artifacts, styles, and probably even themes that are characteristic of the phenomenon. We have yet to find an artifact or style that can be established with reasonable certainty as an import from south of the border, so the economic conclusion is that they were all products of indigenous developments within a vigorous artistic tradition. So, also, there is no reason to search far afield for the inspiration of the iconographies, themes, and ideologies manifested in these artifacts. Whatever resemblance there might be to Mesoamerican iconographies and themes might well be attributed to general underlying ideologies that had been shared by the family of North American Indians from time immemorial, and the expression of which took many different forms through time and space while often sounding many familiar chords." (Brain & Philips 1996)

Although these conclusions were made nearly thirty years ago, this position is still generally accepted. Jefferey Brain, the co-author of those conclusions, said recently, in response to some of the evidence presented here, that he actually does believe there was contact, but that it was "uncoordinated and of little impact". He went on to say that while iconographic comparison may be tempting, cherry-picking designs and motifs without consideration of contextual ideologies, chronology, or mechanisms of transmission are not likely to build much of a case.

“Coincidence, independent invention, even similar expressions of beliefs deeply held through millennia are more viable explanations. In other words, we need actual Mesoamerican artifacts in good Southeastern contexts and evidence of stylistic influence and other lifestyle changes. Otherwise, all we have are a hint of possible vague influences -- tempting but not definitive” (Brain, Personal Communication 2019).

Others may acknowledge the importance of the topic, but only make reference to the suggestion. Rarely do they present any of the ideas that have actually been explored on the subject, much less pursue it in their own research. As Richard Townsend put it in 2004:

"In this period, there are suggestive indications of contact with Gulf Coast peoples of Mesoamerica, but substantial archaeological proofs have proven elusive, and this major issue remains to be fully investigated" (Townsend 2004).

Most posit that the influx of new agricultural technology ( i.e. maize and bean) was most likely imported via the Southwest. The most significant weight given to this argument being that no archeological or physical remains (to date) of Mesoamerican origin have been found in association with Mississippian sites; and conversely, nothing (to date) of Mississippian origin has been found in Mesoamerica. There is the isolated case of a small piece of Mexican obsidian found at Spiro Mounds, but on its own, offers little evidence for significant interaction (Barker, Skinner, Shackley, Glascock, and Rogers, 2002).

With such limits in place, our potential for understanding this important time period has been severely restricted. It also ignores the long established history of tobacco, sunflower, calabash, and squash in the Western Hemisphere and how each was dispersed across two continents centuries prior to the period examined here. More importantly, it underestimates native people and the extent and complexity of their ancient interactions.

The nail in the coffin for the study of the Southwest in isolation was the physical, archeological evidence of scarlet macaw remains and cacao residue on ceramic vessels (Crown & Hurst 2009). While Jeffery Brain is wrong about the absence of a widespread “cult” or religious movement and the "stylistic influence and other lifestyle changes," he and Richard Townsend are right about the ultimate proof. We need the physical evidence of “actual Mesoamerican artifacts in good Southeastern contexts''.

This would go in both directions of course, so any archeological evidence of Midwestern or Southeastern artifacts in Mesoamerica would also apply. This just reinforces the argument that more of those with knowledge of traditional native culture and those that study Mesoamerica, Northern Mexico, and the Southwest should be involved in the examination of the Mississippian Era. There is a deep connection here with the the art and myth of the Midwest and Southeast and numerous aspects of Mesoamerican maize mythology. We see and hear echoes of both the Maya people of the Gulf Coast and various people of central Mexico.

Flowers and Feathered Serpents. (Holms 1881)

Maize Bringers

On the right, is a Mississippian gorget found in northeastern Arkansas, placing it right in the heart of the Mississippian world. While it was included in the most comprehensive catalog of Mississippian gorgets to date (Brain & Philips 1996) and one of the most popular publications on the Mississippian Era (Towsend 2004), it has never been appreciated for its immense potential in our understanding of the complex sharing of cultures during this period.

The well known "Mississippian standard jar'' forms the breast of this uniquely feathered serpent. In its talons are the heads of twins with mouths depicted like those shown on fish in other Mississippian art. Its wings appear to be flowers with spider webs, the upper limbs of which emerge from the jar as snakes marked with concentric circles. The ends look to form long, birdlike beaks. The head of a being with a long nose and a flowerlike tassel in its mouth emerges from the jar with the snakes. The upper legs of the bird are cross hatched like a serpent or fish.

Most significantly, on the breast of the bird, or more accurately, the Mississippian standard jar, is the unmistakable markings of the K'an cross and Ehecailacocozcatl, the “wind jewel” of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl. This leaves little question as to Mesoamerican influences. The wind jewel and shell spiral is also a feature of the Maya Principle Deity, God D, God N, Chac, GI of the Palanque Triad, Nine Wind of the Mixtec, and Quetzalcoatl of Central Mexico (Martin 2015, Lopez Austin 2019).

Also, the presence of this particular style of jar may be an important clue, as this vessel plays a unique role in the Mississippian world relative to maize. At the Mississippian site of Moundville, Alabama, this ceramic style was specificially used to nixtamalize maize, with the vessel and the plant used together as part of a hominy foodway connected to the ancestors of the people using it (Briggs 2016).

Mississippian "Rosetta Gorget" found in Arkansas. Last known location: Tommy Beutell Collection.

Interestingly, this is how the Mandan also viewed such a vessel. In the early 20th century, it was learned that two clay pots were part of the Old Woman Who Never Dies ceremony conducted at the Nuptadi village. Scattercorn, an elder of the tribe and carrier of the Corn Bundle, said that she heard from her father that the ceremony was one of "rain-making" and that the original bundle contained two pots; one pot was symbolic of the Old Woman, while the other represented her husband. These pots where also used to prepare the corn for the ceremonial feast that followed. This ceremony would only be conducted at the appointed time, when the waterbirds began to return from the south in the Spring (Bowers 1950).

Image: Gorget found at Spiro Mounds, Oklahoma.

In the image on the left, we can see two figures holding this very same pot, also marked with a cross. Smoke, steam, or some substance rises and swirls from each pot, while a spider web marked with a cross sits between. First Mother or Grandmother has often been associated with spiders in many native myths. This same association can be seen on a mural at the great Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan (see image below).

We also see this jar on the back of a being etched on a Mississippian gorget found in Missouri (see image on the right). In a Koasati story about the origin of corn and tobacco (Swanton 1929), a man sets out to find food and "took nothing with him except an earthen pot which he carried on his back." On his journey, he meets two hunters who ask him to cook for them. While they are hunting, he takes his earthen pot and makes it "grow large by snapping his fingers against it, set it in the fireplace filled with water in which he had placed some food, and kept up a fire beneath it until it boiled."

On their next hunt, the two men take the man with them, but they only find corn along a trail after shooting their arrows into the forest. As the man collects the grains along the way, the trail opens up to a bright field filled with ripe corn, where the two men then teach him how to make a corn crib. They also give him some tobacco to plant before they leave. These two men are clearly supernatural beings, and most likely the Twins traveling about in their efforts to teach the people all that they have learned.

Another interesting element of the "Rosetta" gorget above is the “fish twins” in the talons of the being. They are very similar to the fish we find in the talons of Seven Macaw in the ballcourt of the Mayan city of Copán in Honduras (see below). Most Maya scholars believe these fish represent the Maya Hero Twins of the Popol Vuh. In the Codex Borgia of Central Mexico, we see a similar birdlike being with a human head emerging from its breast. Its wings and tail are also marked as water lilies (see below).

After the twins died in Xibalba, the Maya underworld, they were ground up, thrown into the water, and reborn as two fish (Tedlock 1996). In Maya myths of the Gulf Coast, the body of the Maize God is reconstituted by fish. In numerous mythological scenes, the Twins are also shown in association with the Maize God on his own journey of resurrection, with the two acting as assistants on that path (see Kerr image below).

Mississippian gorget found in Missouri. (Holms 1883)

The Rosetta Gorget

Mesoamerican "Wind Jewel" (Photo by Justin Kerr).

The same Mesoamerican "Wind Jewel" is clearly represented on the Mississippian gorget.

Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl wearing his wind jewel. (Codex Borgia)

Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl's wind jewel from the Codex Borgia.

The shell spiral commonly found on Mississippian ceramics. Item found at Rose Mound, Cross County, Arkansas. (Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian, New York)

Quetzalcoatl's twin aspect wearing the same wind jewel.

Reproduction of a facade at Copan, Honduras. Note the spots above the tail feathers and the fish twins in the bird's talons.

Line drawing of "Rosetta Gorget" from Arkansas.

Detail of image from the Codex Borgia depicting a similar birdlike being with wings and body marked as water lilies.

In this image from the Codex Borgia we see Quetzalcoatl also emerging from a jar.

A being emerges from a vessel in a similar manner in this image from a shell found at Spiro Mounds, Oklahoma (Phillips & Brown 1984).

Illustration of a stone carving found at the Maya Post-Classic site of Chechen Itza. (Drawing by Linda Schele)

Painted Maya ceramic depicting a similar being marked with the cross. This is Yax Hal Witz, the First True Mountain, which rose on the day of creation. (Photo by Justine Kerr)

The underside of a stone carving of Quetzalcoatl, found in the Aztec capital, bears the likeness of a similar being called Tlaltecuhtli. The top features a coiled feathered serpent. (Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian)

Stone carving of the Aztec earth deity Tlaltecuhtli.

Note the water lilies on the ankles.

A nearly identical water lily emerges from the mouth of the central figure on the Mississippian gorget.

A flower emerging from the mouth is a common motif in Mesoamerica. In one of the few images of Tezcatlapoca, a flower is seen emerging from his mouth.

Drawing of a mural carved in stone at the Maya site of Bonampak in Chiapas, Mexico. Note the theme, composition, and deities (Maize God in the act of rebirth or emergence from Witz mountain, flanked by two fish twins). (Drawing by Raul Velazquez)

The Twins await their father, Hun Hunahpu, as he is adorned for his return from the underworld. (Photo by Justin Kerr)

The Place of Emergence

Some scholars have proposed that the Mississippian cross or "Cross in Circle" represents the Sun, while others believe it represents the earth and the four directions. It may be that it represents more than a single idea or concept. However, if it is considered in light of its possible connections to the maize myths of Mesoamerica, the Maya Ka'n cross, and the Cross of Quetzalcoatl, there may be a way to glean some understanding of how it was used.

A number of plains tribes used the same cross as a symbol for the Evening Star. The Maya also linked this cross to Venus and the Evening Star. This very same cross was a symbol associated with the Mayan rain god Chac, as well as God N or the "Old God", usually shown on the back of a turtle or conch shell. During the Post-Classic it was associated with Quetzalcoatl, or the Feathered Serpent, and the rain god Tlaloc of central Mexico. In the “rattlesnake” gorget shown earlier on this site, we see the cross on the earth or Mississippian Standard Jar and on the back of the feathered serpent’s neck. In Mississippian iconography, this cross is sometimes found on the front of a jar as shown above.

The cross in circle motif is likely based on the original Maya K’an cross. It is found in association with the Feathered Serpent, the Mississippian incense or medicine bag, the eye in hand motif, the endless scroll, four birds, double birds; etc. It appears to be connected in some way with the primordial acts of creation.

Painting by Greg Harlin. © McClung Museum of Natural History & Culture, The University of Tennessee,

Olmec Earth monster (2400-400 BCE) much like the Maya Witz monster. Note the plants emerging from the four corners. The cross appears to represent an entrance to a cave.

Maya Water Lily Witz monster. Note the plants emerging from the K'an cross. The cross appears to represent a place of origin. Some depictions of Mississippian skulls have the same curled snout. (Drawing by Linda Schele)

Maya ceremonial urn with the K'an cross on the lid.

This image from the Maya region, combines some interesting elements, including the cross, a jaguar deer, and a feathered serpent. (Drawing by Linda Schele)

Along with the cross, the double headed serpent over the wings is in style we find in central Mexico, including the “concentric semicircles” on the serpent’s body. The image above depicting the rain god Tlaloc is a perfect example, as it combines a number of similar characteristics to the Mississippian gorget.

Post Classic depiction of Quetzalcoatl with a bag used to carry incense or seeds marked with a cross. (Codex Borbonicus)

Cross used in the ceramics of the Mimbres culture of the Southwestern United States.

Four feathered serpents swirl around a cross on this image from a shell found at Spiro, Oklahoma.

On this Mississippian gorget, we see the cross at the center of four birds and an "endless scroll". This scroll design is also found in Mesoamerica.

Amapa, Western Mexico. The cross is often associated with waterbirds. (Hill 1996)

Maya Foliated Cross found at Palenque with a K'an cross on the Witz or earth skull. (Drawing by Linda Schele)

Mississippian waterbird serpent. (Shell carving found at Spiro, Oklahoma)

Maize & Creation

Many North American maize myths involve the mysterious death or self-sacrifice of the First Mother (Mooney 1901, Swanton 1929, Tedlock 1996). She either dies voluntarily or her remains are brought back after her death. Her husband, First Father, mourns her loss and he and/or the Twins may travel to the otherworld to retrieve her remains or bring her back to life with their sacred arrows (Dorsey 1905, Beckworth 1938). In the process, they may die as well and/or lose their heads (Dorsey 1905, Radin 1948, Tedlock 1996). The themes of birth, death, and resurrection are woven throughout these myths.

Some form of this story was likely communicated in association with the spread of maize and bean agriculture during the Mississippian Era. We find elements of this tale with peoples spread far and wide, including the Arapaho, Arikara, Assiniboine, Aztec, Blackfeet, Caddo, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Creek, Crow, Dakota, Gros Ventres, Hidatsa, Ho-Chunk, Hopi, Iowa, Kʼicheʼ Maya, Maliseet, Mandan, Mi'kmaq, Mixtec, Omaha, Otomi, Passamaquaddy, Seneca, Shoshone, Ute, and Wichita. Aspects of this story are also depicted in Maya art, especially ceramics. Robert Hall pointed out these similarities to the Ho-Chunk legend of Red Horn and his sons over thirty years ago (Hall 1989). The one unifying factor among all of these groups: Maize.

First Father is usually identified with thunder and/or lightning, as are his sons, the Twins. He is often characterized as a medicine man, with magical powers similar to those of his sons. All three are referred to as “Thunderers” in many stories. First Mother has aspects of young and old. The young Corn Maiden or old Grandmother. She is the provider and protector of the sacred seeds. She may even sacrifice her own body to be dragged across the earth to produce the first maize plants. In some stories, she leads the people to the middle world after creation (Will & Hyde 1917, Beckworth 1938) .

Sometimes, the characteristics of the Twins are manifested in one child or “orphan”, with attributes that are more suggestive of the second twin (Swanton 1929). One twin is usually born normally, while the other is born of blood that had been thrown away in some fashion, usually connected with the mother. Sometimes he is connected with a spring or body of water. This second twin is wild, with a long nose or "tusk" that has to be cut off or worn away (Dorsey 1905, Beckworth 1938).

Note the long noses on beings found across the Mississippian world, including those found on the Rosetta Gorget shown above. This also brings to mind the name Red Horn, as he and one of his sons both carried the name in some Ho-Chunk stories (Radin 1948). This twin is often characterized as a magician. He is able to shape shift and revive himself and others after death. In many versions, both twins are born of magic and can revive people from the dead.

These are the same talents of the Maya Twins described in the Popol Vuh (Tedlock 1996) and those of Quetzalcoatl in Central Mexico. Tohil, a deity of the K'iche Maya, transforms from blood, much like the wild twin, also known as, Blood Clot or Throw Away. The wild twin in the Maya myth is most likely Xbalanque, as the spelling of his name may be associated with the feminine aspect of nature. Smoking Mirror, Tetzcatlepoca, and the Red Dwarf of Maya myth may represent the same idea in other parts of Mesoamerica.

In some versions of the story, the son’s kill the mother, often at her request, and oppose the father. In the Natchez version, the mother is killed after she is lured out of the house by “strange creatures” (Swanton 1929). In the Caddo version, the mother is kidnapped and killed by ogres from the otherworld (Dorsey 1905). The Twins then travel to the otherworld, retrieve her bones, and bring her back to life. The three then return home and reunite with the Father (Dorsey 1905).

Xilonen, the young Mesoamerican Maize Goddess (Credit: Laura Vazquez Rodriguez)

In the Mandan version, a monster with no head and a mouth from shoulder to shoulder, kills the mother after biting her on her pregnant belly. This act leads to the birth of the Twins (Beckworth 1938). Oddly, this is an exact description of the birdlike being on the Rosetta Gorget from Arkansas, as well as some Mesoamerican earth beings like Tlaltecuhtli of the Aztec. One of the Creek stories about the Twins tells the same tale where the creature, called a Kolowa, eats the mother.

Image: Tlaltecuhtli. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

This is similar to events described in the Legend of the Fifth Sun and specific actions performed by Quetzalcoatl, such as retrieving maize from Maize Mountain and bringing the bones of the ancestors from the underworld so that First Mother can grind them with maize and blood to create humanity.

In the Historye du mechique, we are told the story of Mayahuel, a young goddess associated with the maguey plant and fertility. Mayahuel is the granddaughter of the star goddess Tzitzimitl. In the story, Quetzalcoatl sneaks away with her, but they are found by the Tzitzimme, other female goddesses who work alongside Tzitzimitl. Mayahuel and Quetzalcoatl try hiding in a tree, but Mayahuel is seen and cut to pieces. Quetzalcoatl then takes her remains and buries them. From her body, the first maguey plant grows (Miller & Taube 1993).

Maize and beans also emerge from the Corn Mother’s body and grow from her remains or bones. In Maya myth, the First Mother or “Bone Woman” mysteriously disappears at the beginning of the Popol Vuh. In the Maya world today, an ear of corn is often referred to as “our mother” and the seed as bone and teeth, “interred ones”, or “little skulls”. The maize seed found within Maize Mountain may be the buried remains of First Mother (Bassie-Sweet 2000).

While the feminine nature of maize is lost in some versions of the myth and it is a male who represents the maize plant, these males usually have a twin associated with them and many times retain the part of the myth that involves the body being dragged around and left to produce the maize plant. In the end, it may be that it is the First Mother’s remains that both the First Father and the Twins are tasked with returning to the earth as maize seed. On the Maya ceramic bowl shown below, we see the maize god emerging from a cleft in a turtle shell, with a gesture that looks as if he's giving or sharing something with one of the twins, possibly seeds, while the other twin pours water from a pot.

In a Skidi myth, we are informed that Tirawa gave seeds of all kinds to Spider Woman, who lived under the earth, instructing her to grow crops and distribute them among people so that all might have access to the seeds. Another version says that the Sun and Moon had given the seeds to this old woman. For the Skidi, the Evening Star is the Chief power in the west. Four other stars represent the clouds, thunder, lightning, and the winds. Those four stars are supposedly sitting in the west, acting as priests. They are sitting there with a bag full of dried buffalo meat. They are also sitting “with a hill or corn stalks always green, and a place in front of them as the altar” (Murie 1914).

The Cheyenne tell a similar tale about a sacred hill with a spring. Inside this hill, in a cave, lives an old woman. Two young men, dressed as twins, enter this cave where they see corn planted everywhere. The old woman then gives the two men corn seed to bring back for the people to plant (Dorsey 1905, Erdoes &Ortiz 1984).

The Arikara have a creation tradition which says that a god (or goddess) had a garden where corn was growing, and it was from this garden that Mother Corn came to earth to help the people. Their traditions also say that after Mother Corn led the people into the Missouri River Valley, she turned herself into corn and thus provided seed for the people to plant. In one of the Arikara tales, the whirlwind becomes angry at Mother Corn and comes to attack the people. In preparation, they try to protect Mother Corn with a sacred cedar tree and a “black meteoric” stone.

Despite this, Whirlwind is able to injure Mother Corn and in the process she throws out an ear of red corn, then yellow, then black, then white; the four sacred colors of the directions (Dorsey 1904). This is also what happens in some versions of the Maya myth, where four colors of maize are created, with the same directional colors, after Maize Mountain is struck by lightning and broken open (Bassie-Sweet 2000). It should be noted that many native people today refer to the stones used during the sweat lodge ceremony as "Grandfather".

Spider Gorget. Dickson Mounds, Illinois. (Illinois State Museum)

Maize Mountain

In many parts of Mesoamerica, maize was found in or on a sacred mountain. In some stories, the maize is growing on the mountain, or found in a cave or cleft (Bassie-Sweet 1999). This is very similar to some stories told in the north. Mother Corn and the Thunderers are said to live in or on a hill covered in maize. Sometimes a sacred spring flows from within this mountain or hill (Will & Hyde 1917). Among the Pawnee, Arikara, and Wichita - we find echoes of a belief that corn was sent to the earth by gods or goddesses. The Pawnee considered Bright Star, the Evening Star, the mother of all things, and believed that in her garden, in the western skies, the corn was always ripening.

Image: Angel Mounds State Historic Park

Arisa, a leading Skidi Pawnee priest, who died in 1878, told this story about the origin of corn:

Tirawa created or caused to be created a boy and a girl and placed them on earth; they married and had children. Their son followed a meadowlark, the messenger of the four servants of Bright Star: Cloud, Wind, Thunder, and Lightning. The bird led the boy far away and finally to an earth-lodge in which these four servants were sitting. They taught the boy how to live; they gave him the buffalo to kill and a sacred bundle containing seed; they taught him how to make hoes with the shoulder blade of the buffalo and gave him sacred rites. This boy returned to the people and became the head-priest; he kept the sacred bundle of seed, giving the seed to the people in the spring and receiving seed from them again in the autumn (Dorsey 1904).

In Mesoamerica, this mountain is sometimes represented by a skull or turtle shell with a cleft, as if split open. Maize plants often emerge from this cleft. The tool used to split open the mountain or skull is usually the Lightning Ax. The Mississippian Twins are also seen emerging from a cleft in a rattlesnake, carrying seeds and rainmaking paraphernalia. We also find a cleft in the head of the Mississippian “long nosed” god (see images below).

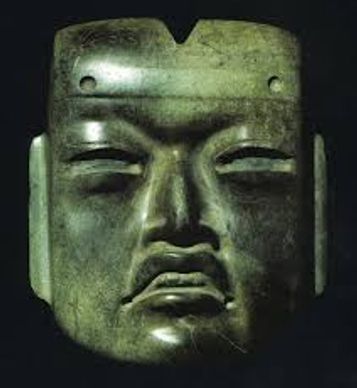

Olmec "Jaguar Baby" with a cleft in the head. The Olmec are recognized as the most ancient of Mesoamerican cultures. (Jade votive axe, 1200-400 B.C.E., Olmec, 29 x 13.5 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum)

Olmec mask (Olmec-style mask), c. 1200 - 400 B.C.E., jadeite, found in offering, buried c. 1470 C.E. at the Aztec Templo Mayor (Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City)

We see a similar cleft in the Mississippian horned rattlesnake from which twin figures emerge.

In one of the most famous images of the Maya Maize God, we see him emerging from a cleft in the shell of a turtle assisted in some way by the Twins. He looks to be handing one seed to be sewn in the quadrilateral earth, while the other provides water from a pot. Just as has been suggested by Karen Bassie-Sweet, he may be returning from the underworld with the remains of First Mother as maize seed. (Photo: Justin Kerr)

Here we see a more traditional and artistically superior version of the Mississippian "long nosed" god, with the long nose, google eyes, and cleft. All of these elements combined suggest a theme of rain and fertility. The nose may actually be the beak of a hummingbird. (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.)

In this detail from a Mississippian gorget we see a flame or grass-like growth emerging from the cleft of a magical being or deified ancestor flanked by twins.

First Mother & The Twins

In a Caddo myth, we are told that the mother disappeared while going to fetch water at a stream (Dorsey 1905). A comparable event occurs in the Maya creation myth when the grandmother also goes to fetch water at a stream. It is there that she is purposely delayed by the Twins. We hear this is the Popol Vuh (Tedlock 1996) and we see it depicted on Maya ceramics (See Justin Kerr image 1254). However, there is something more complete about the Caddo myth as opposed to the Popol Vuh. We know what happened to First Mother in the North, something not entirely clear in the highlands of Chiapas during the Colonial Era, where the Popol Vuh was written.

One of the oldest representations of the Twins can be found on a mural in the ancient Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan (see image on the right). Twin figures flank what appears to be a female deity. What they are engaged in is not entirely clear. Are they assisting the central figure or are they receiving something? They are both holding Mesoamerican incense bags, but they are also engaged in “offering” two different items to the earth: one offers water and the other seed. We find these same traits in art depicting the Hero Twins of the Mississippian Era.

One twin, also known as Thunder Boy, Arrow Boy, or Lodge Boy, may represent aspects of the hunter and the planter, while the other, Lightning Boy, Blood Clot, or Throw Away, may represent the medicine man, magician and rain bringer. From some of the Mississippian iconography, one appears to be the seed carrier and planter and the other the rainmaker.

Mural from the Tepantitla compound at Teotihuacan depicting similar themes found further north.

In the image on the right we see twin-like figures emerging from a cleft in the back or side of a horned rattlesnake. Rattlesnake tails also extend from the back of their shoulders. The twin on the right seems to be associated with rain and water. His tail is marked by water signs. A cross is on his belt and on the tail of a snake he holds in one hand. Based on the markings, this may be a coral snake.

The other twin appears to be associated with seed. You can see him scattering three seeds from one of his hands. His rattlesnake tail is marked with what may be a Mississippian motif for seeds. Both figures’ heads are capped with a five pointed headdress. They each hold a flint knife in one hand. The bundle that both have their hair tied in is almost exactly the style seen in some Mesoamerican art.

The Twins, often led by the younger "wild" twin, disobey their father, mother or grandmother on numerous occasions. They travel to the places they warned them not to go. They fight various monsters, witches or animals and emerge victorious. Sometimes they are killed and must revive themselves before they return home (Mooney 1901, Dorsey 1905, Swanton 1929, Tedlock 1996).

Continues on the following page...

Mississippian image depicting twin beings emerging from a cleft in a horned rattlesnake.

In this Image from the Codex Vienna, two figures named 7 Rain and 7 Eagle using some kind of tool on a mythical female tree, from which the first woman and man emerge, all part of the Mixtec origin myth. Note the twin figures, the objects in their hands, the arrows inside the tree, and the woman's head.

.

This image is from a Mississippian gorget found at Spiro, Oklahoma. Twin figures stand next to what appears to be a tree containing bows and a head with a cleft from which something seems to emanate. Note the object they hold in their hands and thrust against the tree.

The oval motif found on the horned rattlesnake and the rattlesnake "cape" of the seed bearing twin is remarkably similar to a dented maize seed or split bean seed.

"...he said that they should have a red bean for a symbol to show that they could slip out of the hands of their enemies, and they painted the red beans on their shields. Then he placed two young men ahead of all the Brave Warriors and he said that these two would be the defenders of the society and the village. He placed a sunflower stalk in the hand of each one..." -Good Fur Robe (Mandan)

Evening Star Project

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience.